From Memphis Belle to The Cold Blue: The B-17 and the Treasure of WWII Archival Footage

February 10, 2020 | by Jay Stowe

The Second World War can claim a number of firsts—the vast majority of which live in infamy to this day. But being the first major war documented exhaustively on film has an occasional upside. Case in point: 15 hours of raw color footage revealing what it was really like to be a crewman on a B-17 Flying Fortress in the skies over Europe.

The moment Erik Nelson stumbled upon the 34 reels gathering dust in the bowels of the National Archives, he knew he’d struck cinema gold. A producer and director whose specialty is historical documentaries, Nelson had been sent on a “spelunking expedition” funded by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen’s production company to uncover color footage of World War II airplanes for Allen’s Flying Heritage and Combat Armor Museum in Everett, Washington. He found the film—originally shot by famed Hollywood director William Wyler—within a day of starting his research.

“It was hiding in plain sight,” Nelson says. “My reaction watching the footage was akin to when Howard Carter opened up the tomb of King Tut: ‘Yes, [I see] wonderful things.’ When I saw it, I knew exactly what I could do with it.”

What he did with it was create a brand-new big screen documentary, The Cold Blue, timed to coincide with the 75th anniversary of D-Day last year. The Cold Blue is currently available on HBO Now.

A Story Unto Itself

The origin of those 15 hours of film is a story in itself. When the war broke out, a number of Hollywood directors—John Ford, John Huston, and Wyler, among others—offered their services to the U.S. military to help with the war effort. Wyler had emigrated from Europe before the war and worked his way up the motion picture studio system to become an A-list director. He was also Jewish and had relatives in Europe, so he had more than a passing personal interest in seeing the war up close.

Attached to a bomber group in the 8th Air Force stationed in England in 1943, Wyler fast-talked the top brass into letting him and a small crew of cinematographers ride along with the air crews on their missions over Germany and other parts of Europe. Wyler “started filming first and figuring out the story later,” says Nelson. The result was a documentary called The Memphis Belle. Originally released in April 1944, the film follows the exploits of one B-17 crew as they thread the needle, completing 25 missions safely before rotating back to the states on a publicity tour to raise war bonds.

As his daughter (and executive producer) Catherine Wyler says in a short video about the making of The Cold Blue, “He didn’t want to miss a big, thrilling thing like World War II. I think he was something of a daredevil. He said that once you got up into the plane and were taking pictures, you forgot that people were shooting at you.”

Shooting film while being shot at is not easy, of course. The Cold Blue is dedicated to Harold Tannenbaum, one of Wyler’s cameramen, who was killed on a mission. Indeed, the casualty numbers are staggering. According to the film, 135,000 men served in the 8th Air Force; they flew three million missions over the course of the war and 28,000 were killed in action.

Nelson made a point of tracking down and interviewing nine airmen—pilots, gunners, and bombardiers—who survived the war. They are in their 90s now and when they look back at what they endured, it’s with clear eyes. Nothing is sugarcoated. To begin with, the conditions they flew under were harsh: the B-17s were neither pressurized nor heated, and temperatures could drop to 60 degrees below zero. As impressive as hundreds of B-17s flying in tight formations look—and the footage of them soaring against bright blue Technicolor skies is a soul-stirring sight—their daytime missions made them easy targets for deadly anti-aircraft fire and German fighter planes.

“On a clear day, the Germans could see us [coming] 50 miles out because of the contrails,” says one vet in the film. “And that wasn’t good, because when that happened they were ready for us.”

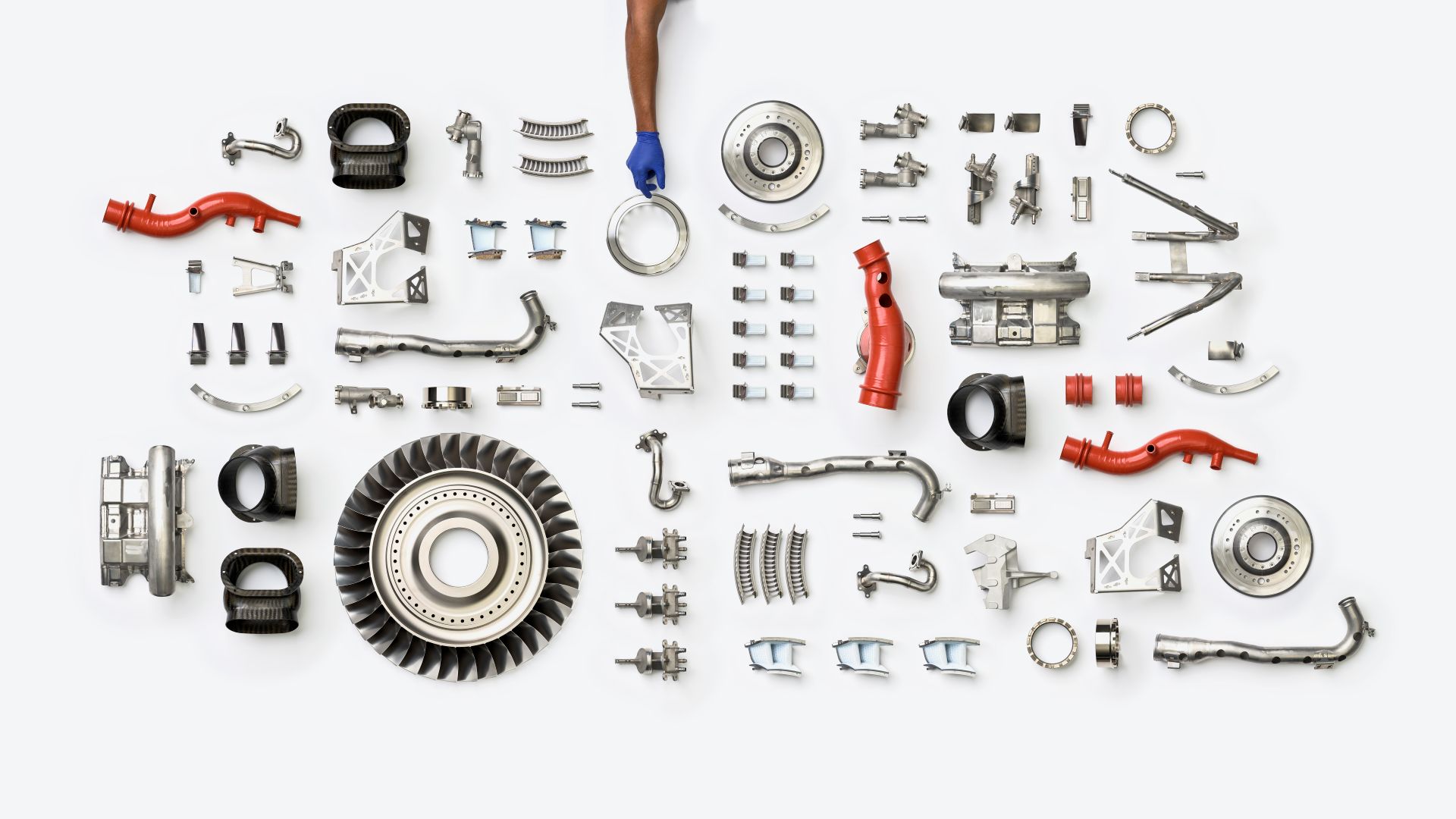

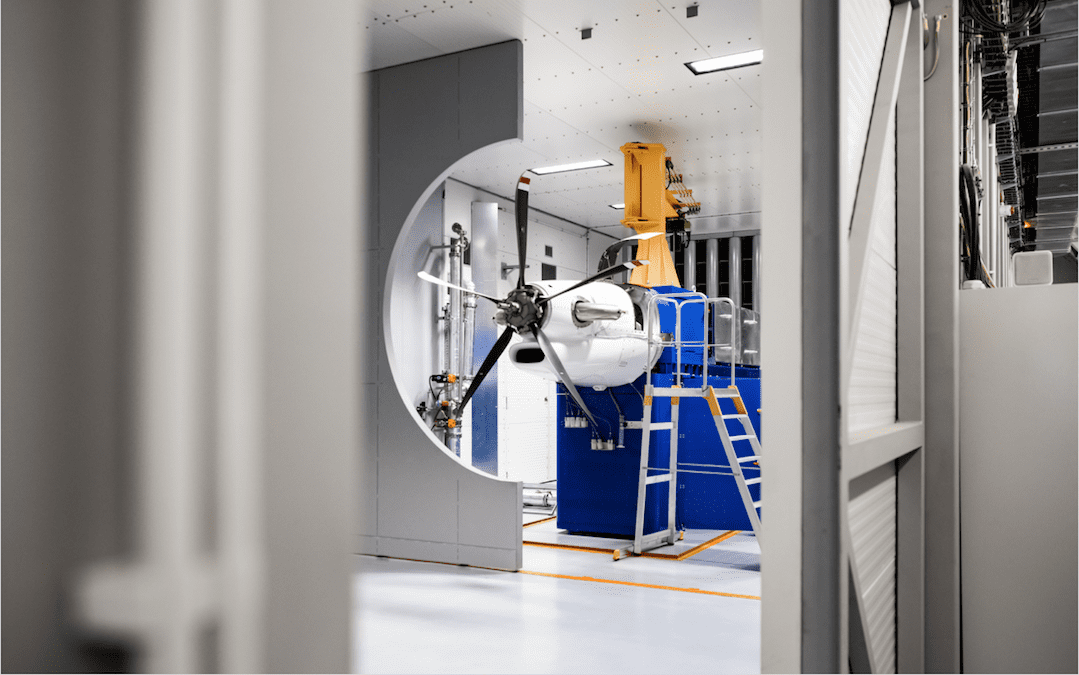

The B-17 and the GE Turbosupercharger

Still, the veterans in the film have generally positive recollections of the planes they flew. Made by Boeing and powered by four Wright R-1820-9 Cyclone engines equipped with GE turbosuperchargers, the B-17 “flew like a dream, like an overgrown Piper Cub,” another vet recalls. By 1945, more than 12,000 of them had been built—which translates to tens of thousands of engines and turbosuperchargers produced at GE’s facility in Lynn, Massachusetts and the Wright plant in Evendale, Ohio (now Building 700 on the GE Aviation headquarters campus).

“The B-17 engines were an unbelievably reliable and steady and battle-tested piece of machinery,” says Nelson. “They kept running and they brought many a pilot back, sometimes with only two engines, and in some cases only one engine, [still working].”

It took Nelson and a small team of filmmakers about 18 months to make the documentary. Much of that time was devoted to restoring the original footage—shot mostly on professional 16mm cameras and some smaller, home movie-style cameras passed out to crewmen—and transferring it to a format that allowed the film to be viewed on a wide screen without loss of detail.

“The color was still in our footage but it had faded and there were scratches and dirt and it looked terrible,” says Nelson. “It was very carefully color corrected. Every shot had its own challenge.”

After removing the dirt and damage digitally, Nelson and his team were able to “take it from the 16mm raw footage and put it on 4K video at the National Archives and then blow it up to wide screen.” In addition to cleaning up the film used for The Cold Blue and adding sound effects (no original audio recordings were made by Wyler and his team), they fully restored The Memphis Belle in time to show it at the unveiling of the newly refurbished namesake B-17 at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force at Wright Patterson Air Force Base in May 2018.

A self-described “airplane nerd,” Nelson is proud of the fact that he was able to rescue William Wyler’s original footage and give it a new life. But when asked if he had an emotional reaction the first time he viewed the recovered film, he had a simple answer: No. Having made military documentaries for the last 30 years and interviewed countless survivors of some of history’s greatest tragedies, “it takes a lot to get me emotional,” he says. His goal with The Cold Blue was to “create a feeling of what it was like to do it”—to have served as an airman in one of most prolonged and dangerous engagements in World War II.

“It’s always just a challenge to showcase [the story] and bring it out,” Nelson adds. “It’s not my job to be emotional; it’s my job to make other people emotional.”

The moment Erik Nelson stumbled upon the 34 reels gathering dust in the bowels of the National Archives, he knew he’d struck cinema gold. A producer and director whose specialty is historical documentaries, Nelson had been sent on a “spelunking expedition” funded by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen’s production company to uncover color footage of World War II airplanes for Allen’s Flying Heritage and Combat Armor Museum in Everett, Washington. He found the film—originally shot by famed Hollywood director William Wyler—within a day of starting his research.

“It was hiding in plain sight,” Nelson says. “My reaction watching the footage was akin to when Howard Carter opened up the tomb of King Tut: ‘Yes, [I see] wonderful things.’ When I saw it, I knew exactly what I could do with it.”

What he did with it was create a brand-new big screen documentary, The Cold Blue, timed to coincide with the 75th anniversary of D-Day last year. The Cold Blue is currently available on HBO Now.

A Story Unto Itself

The origin of those 15 hours of film is a story in itself. When the war broke out, a number of Hollywood directors—John Ford, John Huston, and Wyler, among others—offered their services to the U.S. military to help with the war effort. Wyler had emigrated from Europe before the war and worked his way up the motion picture studio system to become an A-list director. He was also Jewish and had relatives in Europe, so he had more than a passing personal interest in seeing the war up close.

Attached to a bomber group in the 8th Air Force stationed in England in 1943, Wyler fast-talked the top brass into letting him and a small crew of cinematographers ride along with the air crews on their missions over Germany and other parts of Europe. Wyler “started filming first and figuring out the story later,” says Nelson. The result was a documentary called The Memphis Belle. Originally released in April 1944, the film follows the exploits of one B-17 crew as they thread the needle, completing 25 missions safely before rotating back to the states on a publicity tour to raise war bonds.

As his daughter (and executive producer) Catherine Wyler says in a short video about the making of The Cold Blue, “He didn’t want to miss a big, thrilling thing like World War II. I think he was something of a daredevil. He said that once you got up into the plane and were taking pictures, you forgot that people were shooting at you.”

Director William Wyler (center), photographed during his time filming the 8th Air Force, with two of his cameramen—William Clothier (right) and William Skal (in plane window). British war correspondent Cavo Chin is on the left.

Director William Wyler (center), photographed during his time filming the 8th Air Force, with two of his cameramen—William Clothier (right) and William Skal (in plane window). British war correspondent Cavo Chin is on the left.

Shooting film while being shot at is not easy, of course. The Cold Blue is dedicated to Harold Tannenbaum, one of Wyler’s cameramen, who was killed on a mission. Indeed, the casualty numbers are staggering. According to the film, 135,000 men served in the 8th Air Force; they flew three million missions over the course of the war and 28,000 were killed in action.

Nelson made a point of tracking down and interviewing nine airmen—pilots, gunners, and bombardiers—who survived the war. They are in their 90s now and when they look back at what they endured, it’s with clear eyes. Nothing is sugarcoated. To begin with, the conditions they flew under were harsh: the B-17s were neither pressurized nor heated, and temperatures could drop to 60 degrees below zero. As impressive as hundreds of B-17s flying in tight formations look—and the footage of them soaring against bright blue Technicolor skies is a soul-stirring sight—their daytime missions made them easy targets for deadly anti-aircraft fire and German fighter planes.

“On a clear day, the Germans could see us [coming] 50 miles out because of the contrails,” says one vet in the film. “And that wasn’t good, because when that happened they were ready for us.”

The B-17 and the GE Turbosupercharger

Still, the veterans in the film have generally positive recollections of the planes they flew. Made by Boeing and powered by four Wright R-1820-9 Cyclone engines equipped with GE turbosuperchargers, the B-17 “flew like a dream, like an overgrown Piper Cub,” another vet recalls. By 1945, more than 12,000 of them had been built—which translates to tens of thousands of engines and turbosuperchargers produced at GE’s facility in Lynn, Massachusetts and the Wright plant in Evendale, Ohio (now Building 700 on the GE Aviation headquarters campus).

“The B-17 engines were an unbelievably reliable and steady and battle-tested piece of machinery,” says Nelson. “They kept running and they brought many a pilot back, sometimes with only two engines, and in some cases only one engine, [still working].”

It took Nelson and a small team of filmmakers about 18 months to make the documentary. Much of that time was devoted to restoring the original footage—shot mostly on professional 16mm cameras and some smaller, home movie-style cameras passed out to crewmen—and transferring it to a format that allowed the film to be viewed on a wide screen without loss of detail.

“The color was still in our footage but it had faded and there were scratches and dirt and it looked terrible,” says Nelson. “It was very carefully color corrected. Every shot had its own challenge.”

After removing the dirt and damage digitally, Nelson and his team were able to “take it from the 16mm raw footage and put it on 4K video at the National Archives and then blow it up to wide screen.” In addition to cleaning up the film used for The Cold Blue and adding sound effects (no original audio recordings were made by Wyler and his team), they fully restored The Memphis Belle in time to show it at the unveiling of the newly refurbished namesake B-17 at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force at Wright Patterson Air Force Base in May 2018.

A self-described “airplane nerd,” Nelson is proud of the fact that he was able to rescue William Wyler’s original footage and give it a new life. But when asked if he had an emotional reaction the first time he viewed the recovered film, he had a simple answer: No. Having made military documentaries for the last 30 years and interviewed countless survivors of some of history’s greatest tragedies, “it takes a lot to get me emotional,” he says. His goal with The Cold Blue was to “create a feeling of what it was like to do it”—to have served as an airman in one of most prolonged and dangerous engagements in World War II.

“It’s always just a challenge to showcase [the story] and bring it out,” Nelson adds. “It’s not my job to be emotional; it’s my job to make other people emotional.”