The most important private and business aviation event in Europe, EBACE 2023, was staged in the city of Geneva last month, gathering the industry’s top players along with their latest developments and flagship products.

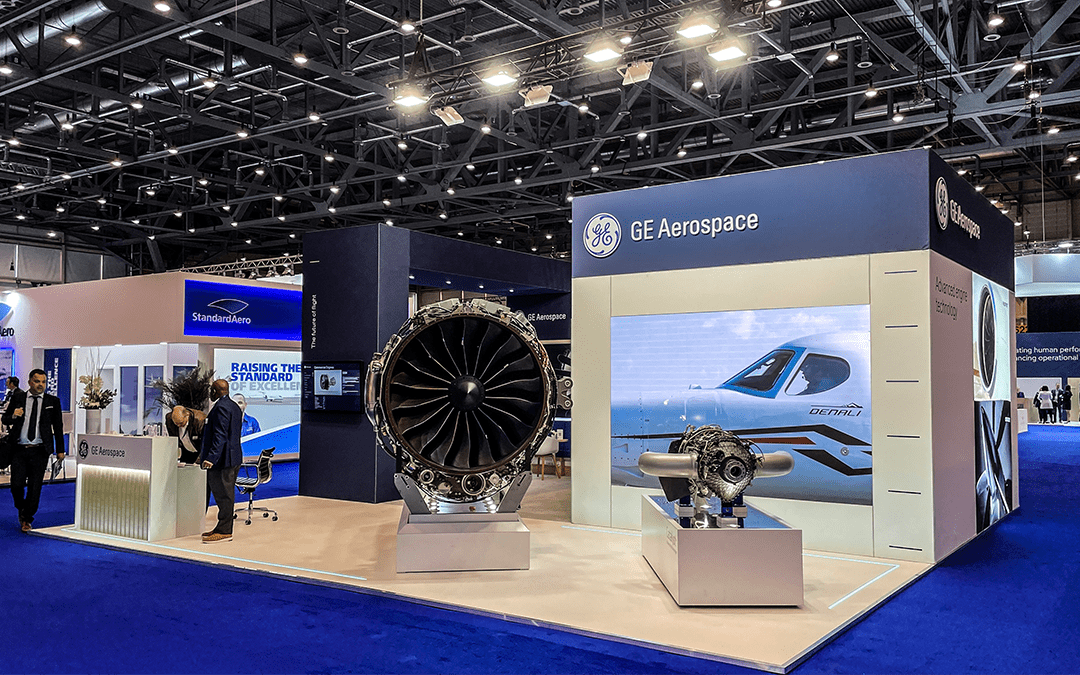

Among the flagship products on display were full-scale mockups of GE’s Passport engine and the new Catalyst turboprop engine, a product of Avio Aero - a GE Aerospace company.

As a relatively new entrant to the business aviation space, the Passport engine is already making waves. With more than 250 engines in service, it has accumulated nearly 200,000 service hours since its introduction on Bombardiers Global 7500 in 2018. It has since also been named the powerplant for the new Bombardier Global 8000.

“The success of the GE Passport engine is in large part thanks to our commercial learnings which we applied to this product design,” said Melvyn Heard, the business aviation product line leader for GE Aerospace. “The hugely successful CFM LEAP engine, which now has more than 20 million total hours, was leveraged to develop the core architecture and we expect to keep setting the pace for the business aviation market with this engine.”

The game changing Catalyst is working to follow in those same footsteps as it progresses towards a service introduction on the Beechcraft Denali, by Textron. The Beechcraft Denali’s flight test campaign is moving forward and has thus far carried out 700 flights and accumulated more than 1,300 hours in the air.

The Passport and Catalyst engines on display at the GE Aerospace booth.

The Passport and Catalyst engines on display at the GE Aerospace booth.

“We’re very pleased with all the work put into designing this engine,” says Chief Test Pilot, Dustin Smisor, confirmed expectations about flight progress and exciting performance reviews. “It’s been extremely solid and reliable. Seeing its fuel efficiency, I’ve had to re-gauge myself because it doesn’t burn a lot of fuel”.

According to Smisor, the Catalyst and Denali are the perfect match.

“We as test pilots go well above and beyond what normal pilots go through,” he added. “This includes testing in-flight shutdowns, rapid accelerations and decelerations of power, as well as extreme conditions.”

Paul Corkery, Catalyst Program Leader at Avio Aero, also noted how much the technological innovation and the firsts encapsulated in the new engine.

"We are at about 72 percent with engine certification testing. So far we have assembled 26 engines and achieved more than 5,500 hours of operation - counting ground and flight tests." Corkery said, about the company’s target for completion in 2024.

This is no small feat as the last clean sheet turboprop engine to be certified was more than 50 years ago, and a lot changed with the certification process since then.

“We’re undertaking the most rigorous process ever faced by a turboprop engine and its single components, with several new regulatory requirements: such challenge relates also to the serial production ramp-up during years marked by major shocks running through the global supply chains and logistics” adds Corkery.

Experts and engineers at work in the European Avio Aero and GE Aerospace sites, as well as on the flight campaign field at the test center in Wichita (at Textron Aviation’s headquarters), know this well. Among those in Prague, Jiri Pecinka has spent the last few years with mind and heart on this engine. He was at the airport in Berlin when it lifted off for the first time, as well as during its first ignition on the threshold of 2018 in Prague.

"My most intense memory is still related to FETT(the first ever ignition, ed.)," said Pecinka, Test System Engineering Section Manager. "If you will, a simple test for experts: just start the engine and get it to idle. But that was the first time in decades that a powertrain featured never-before-seen innovations, designed and built from scratch. Today it is now routine for us, so even the various tests we carry out - including new and complex, like ice crystal icing tests (for ice formation at high altitudes, ed.) or the more delicate ones where you test it by simulating borderline, very critical situations - must ensure both operability and safety."

Pecinka and his colleague Validimir Ostrovsky are in Prague, home to a large group of engine’s modules designers and engineers who are part of a much larger team that sits across Turin, Brindisi, Bielsko Biala, Warsaw, and Munich and numbers up to 300 engineers. When they talk about their work, they act as if their colleagues from these cities were in the next room.

"Collaboration between all sites takes place through lines of communication and tools typical of our standard work, an integral part of the lean culture in GE, and covers the preparation and execution of tests. Daily meetings in every location, in every team in every business function, report from individual instrumentation or planning needs to the most complex problems to be solved," said Ostrovsky.

"Most of it is done remotely with the different European locations, and this has made our transition between pre-Covid and post-Covid ways of working a little easier. And the more informal, rapid line of communication is equally crucial. It is now more common to see in person, which facilitates problem solving, shortens time, and especially helps new, perhaps younger, team members with alignment, learning. Relationships are stronger and more engaging, and this makes you feel like one team at the expense of distance," Pecinka said.

It is a team effort that produces effects on those experienced pilots overseas who know what it means to make aircraft and engines from a blank sheet of paper, as Smisor testifies. “We have made incredible progress. It’s extremely simple to operate this aircraft. When you step inside the cabin and cockpit, it gives you a jet-like experience. It’s a lot of fun to fly, a workhorse, and a great cross-country airplane.”