GE’s Most Versatile Fighter Engine is Ready for the Next Generation of U.S. Air Force Pilots

October 7, 2020 | by Cole Massie

Concealed within the F-117 were two F404-GE-F1D2 engines. The F404, originally selected by the U.S. Navy in 1975 to power the McDonnell Douglas (now Boeing) F/A-18 Hornet, made an ideal candidate for the F-117. Affordable, lightweight, and offering ample thrust for the platform, a small number of F404s destined for those U.S. Navy F/A-18s were strategically plucked from GE’s Lynn, MA, assembly line, equipped with special modifications, and rerouted to Burbank, California, where Lockheed Martin was building F-117s in secrecy.

Despite the F404 being capable of supersonic propulsion, as demonstrated on the Hornet, the Nighthawk was notably restricted to subsonic speeds—the afterburners required to break the sound barrier would negate the aircraft’s stealth properties. GE engineers helped design the F-117’s unique exhaust, which was meant to diffuse the hot air leaving the engine and evade both radar and heat-seeking missiles.

Above: The F-117 Nighthawk’s exhaust is one of the unique in all of aviation, and it helped the aircraft retain its stealth properties. Credit: Lockheed Martin. Top: Boeing/Saab T-7A Red Hawk, powered by GE’s F404-GE-103 engine. Credit: Boeing

Above: The F-117 Nighthawk’s exhaust is one of the unique in all of aviation, and it helped the aircraft retain its stealth properties. Credit: Lockheed Martin. Top: Boeing/Saab T-7A Red Hawk, powered by GE’s F404-GE-103 engine. Credit: Boeing

With all these modifications, the F404 gained a one-word reputation: versatile.

In the more than 40 years of the F404 program’s life, variants of the engine have powered 15 different production and prototype aircraft. Among the most well-known are the aforementioned F-117 Nighthawk and F/A-18 Hornet, but international programs, including KAI’s T-50 Golden Eagle, HAL’s Tejas Mk1, and Saab’s JAS 39 Gripen continue to perform with F404 power today.

Some remarkable prototypes also went through their paces with the F404. Grumman’s forward-swept wing X-29 completed 437 flights between 1984 and 1992. Northrop’s successor to its F-5 Tiger, the F-20 Tigershark, was a fan favorite, but failed to attract customers before the program was mothballed. Two Rockwell/MBB X-31 prototypes were tested from the early- to mid-1990s to study thrust vectoring.

It’s a strong history of performance, but don’t let that 40+ year history fool you: the F404 is anything but an “old” engine.

Chosen to power the next generation of U.S. Air Force pilots through a rigorous flight training program, the Boeing/Saab T-7A Red Hawk is powered by the F404’s newest variant, the F404-GE-103, and this new application is poised to keep these engines in the sky well into the future.

The distinct red tails on the T-7A pay homage to the Tuskegee Airmen, a group of primarily African American pilots, engineers, technicians and others, who were famous for the red-painted tails on their World War II fighters. Credit: Boeing

The distinct red tails on the T-7A pay homage to the Tuskegee Airmen, a group of primarily African American pilots, engineers, technicians and others, who were famous for the red-painted tails on their World War II fighters. Credit: Boeing

GE Aviation employees Adam Donofrio, Justin Woodfall, and Josh Siegel work with the -103 every day. From day-to-day problem-solving dedicated to a successful T-7A flight test campaign, to looking out into the future for potential market opportunities, they’re all intimately involved with the -103 and excited about the performance it can deliver.

“We’ve demonstrated the ability to integrate this engine into all different types of aircraft with different inlets and different exhaust systems,” Donofrio, the T-7A Product Director, pointed out. “Back at the start of the F404 program, the engineering team designed and pushed this engine to the limits. That’s set us up for success today, where, for example, with the T-X competition, we were well positioned based on decades of knowledge and experience in this thrust class.”

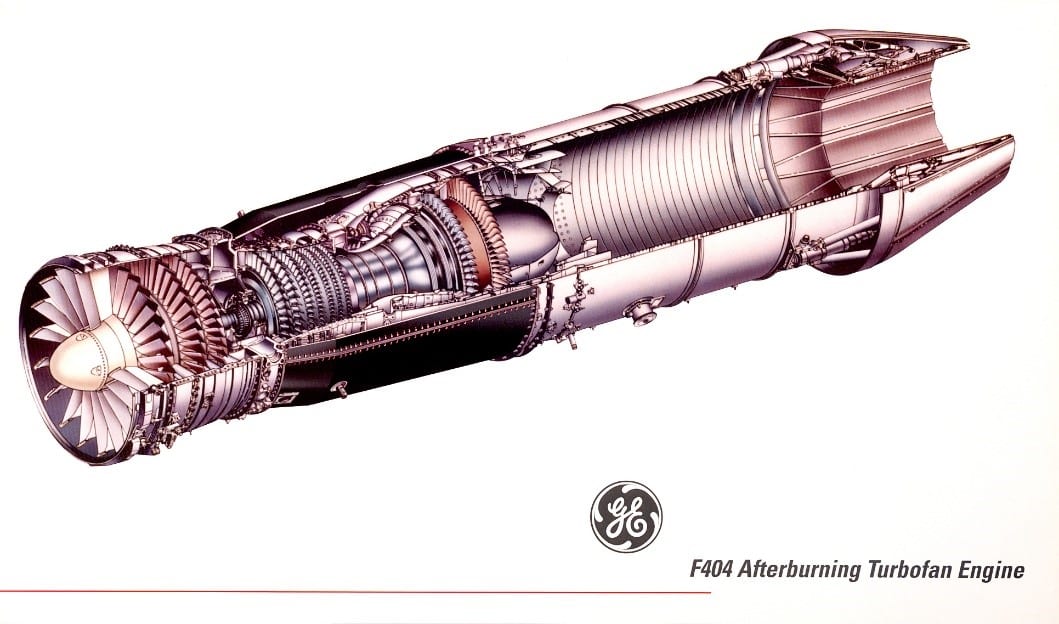

A 1970s-era cutaway of the F404 that powered the F/A-18 Hornet, designated the F404-GE-402. Credit: GE

A 1970s-era cutaway of the F404 that powered the F/A-18 Hornet, designated the F404-GE-402. Credit: GE

In addition to Boeing/Saab’s offering for the T-X competition, Lockheed Martin/Korean Aerospace Industries’ T-50 entry and Northrop Grumman’s Model 400 entry also featured F404 power.

Woodfall, GE’s T-7A Engineering Platform Leader, highlighted the -103’s modernization and single engine safety features, including its Full Authority Digital Engine Control (FADEC), as key differentiators in the engine’s performance. The FADEC, for example, allows for an assortment of benefits, namely advanced engine health monitoring and enhanced engine diagnostics.

“Previous F404 variants did not require or have as much digital capability,” Woodfall said. “We’re excited how we can use this FADEC capability and modernization to provide the U.S. Air Force with advanced digital health monitoring, which aligns with requirements for the fighters of the future.”

Another huge consideration for the customer is maintenance, Siegel, the T-7A program manager, mentioned. Maintainability can allow engines to remain operable for extended periods of time. Take, for instance, the T-7A’s predecessor and one of the Air Force’s current trainers, the T-38C Talon. The T-38, powered by GE’s J85 engine, took its first flight in 1959—more than 60 years ago.

A J85-powered T-38C Talon trainer takes off in full afterburner. Credit: U.S. Air Force photo by Danny Webb. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

A J85-powered T-38C Talon trainer takes off in full afterburner. Credit: U.S. Air Force photo by Danny Webb. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

“That longevity can’t happen without maintainability,” Siegel noted. “Another benefit with the F404, is its modular design which gives operators additional maintenance flexibility, lower maintenance costs and better time-on-wing.”

The -103 is currently being put through its paces as part of the T-7A flight test campaign. It’s a rigorous process, but nothing the F404 hasn’t seen before.

“We have 40 years’ experience telling us the engine will perform. It’s the integration with the airframe that we’re really focused on during flight tests,” Donofrio said. “We want to make sure the engine and airframe are completely in sync.”

It’s been on display, too. Boeing has recently highlighted both a single-engine air start and inverted flight maneuvering to push the trainer to its limits.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N84KveYcAGM

It will be several years before the T-7A officially begins replacing the T-38 in U.S. Air Force training squadrons. But Donofrio, Woodfall, Siegel, and the F404 team based out of GE’s Lynn, MA, plant know every day spent improving this product is worth it.

“There’s really an opportunity here to repeat what we did with the J85,” Donofrio said. “That engine-airframe combination has been around for 60 years, and I think we’d be thrilled with another 60 with this F404. We’re really excited about how this engine will perform as it powers future generations of Air Force fighter pilots through training.”