Laser Focus: New Documentary Celebrates the Long and Fruitful Career of GE Research’s Dr. Marshall Jones

February 27, 2024 | by Maggie Sieger

Growing up on the North Fork of Long Island after the Second World War, Marshall Jones didn’t know any Black people who had gone to college. The great-uncle who helped raise him labored on a duck farm. His classmates at Aquebogue Elementary School aspired to be farmers as well, or athletes. Jones, though, dreamed of piloting jets like the ones he saw flying over his house from the nearby Grumman Aircraft factory. When his nearsightedness prevented him from doing that, he chose a different path, becoming one of just 12 Black PhD engineers in the entire United States as of the early 1970s and landing at GE Research in 1974. Fifty years later, the pioneering laser scientist from the east end of Long Island has earned 70 patents as a mechanical engineer — and he’s not through yet.

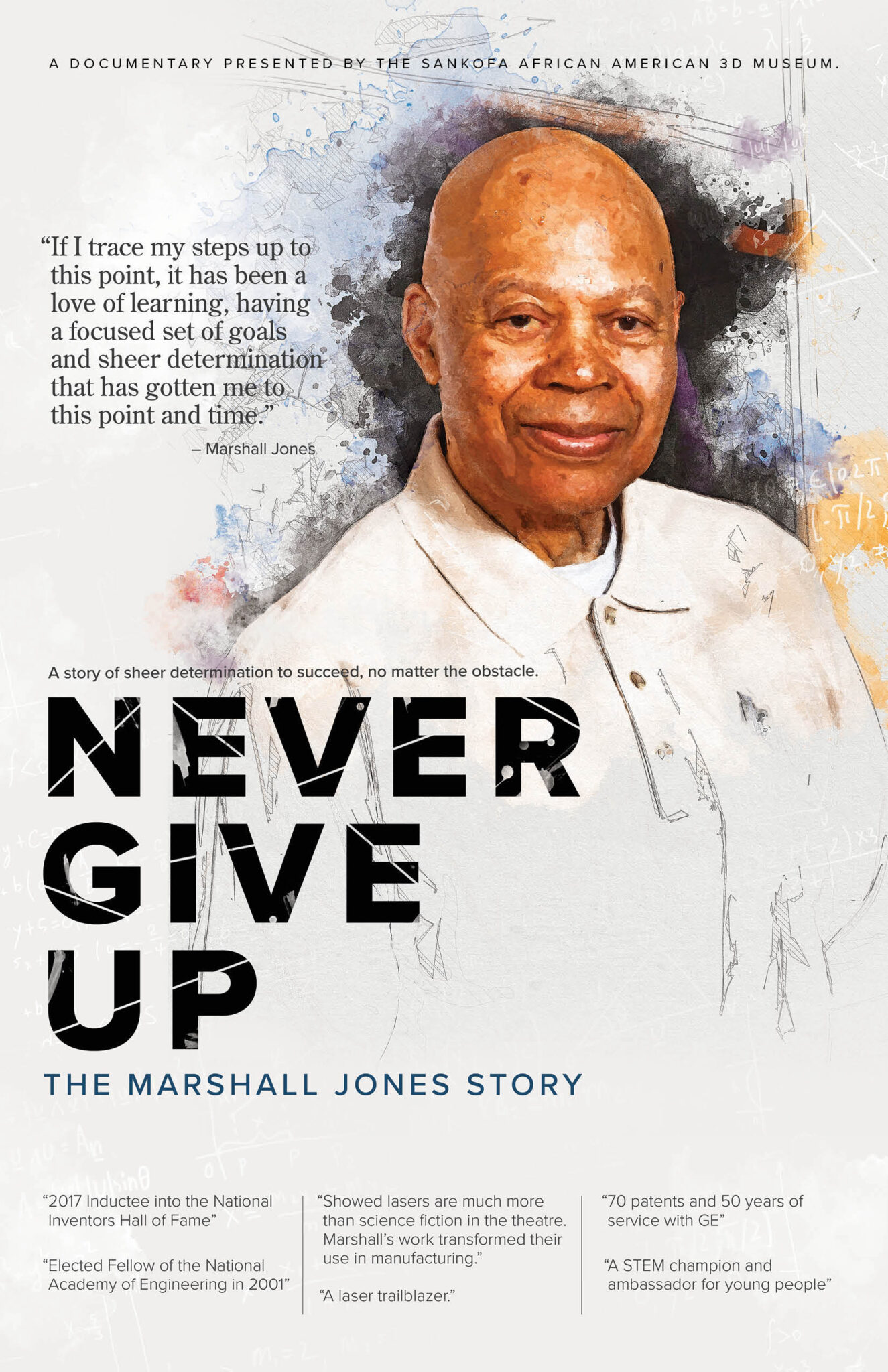

Jones’s story of perseverance, hard work, and a drive to make a difference is being told in a new documentary about his life called Never Give Up: The Marshall Jones Story, making its premiere at the GE Theatre at Proctors, in Schenectady, New York, on Feb. 28. The title of the film, which is presented by the Sankofa African American 3D Museum, comes from Jones’s own mantra to “never give up,” no matter what life throws at you. It’s a message he’s lived by and brought to countless students and young engineers over decades as both a motivator and a mentor.

Marshall Jones was raised by Mary Miller, his grandmother’s sister, and her husband, Lawrence, who worked the duck farm in Aquebogue. (Jones’s father was serving in the Navy, and his mother worked as a seamstress in New York City.) Lawrence Miller taught the young boy how to fish, cook, and do math in his head, but mostly Miller encouraged him to dream. “I looked up to him in a big way,” Jones says. “He thought that maybe I could do something more with my life.”

When Jones got to the end of his fourth-grade year, his teacher told him he’d have to repeat the grade. He strongly disagreed: After all, he was a whiz at math and science, not to mention a talented athlete. But Mrs. DeFriest, his teacher, thought his reading skills needed work, and his aunt and uncle took her word over that of the disgruntled boy.

Today Jones says that if he hadn’t been forced to stay back, he wouldn’t have become an engineer. That year he spent catching up on his reading and spelling, he says, laid the foundation for all the successes that have followed.

“It was a tough pill to swallow,” Jones says of joining a class that included his younger brother. “But everything came from that. I learned to never give up.”

Engineering His Future

That same determination to succeed kept Jones going when a knee injury cost him a wrestling scholarship to college. A community college in upstate New York was all he could afford, but he used that springboard to get himself to the University of Michigan, where he earned an engineering degree, and from there to the doctoral program in mechanical engineering at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst. His resolve also helped him overcome smaller hurdles, like when the left-hander discovered that all the tools necessary for his first internship were designed for right-handed people. And it carried him over bigger ones, like the discrimination he experienced through the years, including being denied housing and entry to hotels because of his race.

An adviser at UMass, who was retired from GE Research, pushed Jones to consider the labs in Schenectady, but his first interview didn’t go as expected. Somehow, the newly minted PhD in mechanical engineering ended up interviewing for a job with a bunch of materials science engineers and decided against taking the job. Although interested, Jones wasn’t willing to compete against engineers who had a 10-year head start over him in materials engineering. But a few months later he went back to interview for a different job with a small group of mechanical engineers based in GE’s legendary research facility, Building 37. It was Marshall who began working on lasers, bridging work there with ongoing laser technology programs happening a few miles up the road at GE’s research campus in Niskayuna.

“GE was using high-powered lasers for defense work in Binghamton [New York], and I thought that if we could use them, we could do some things that hadn’t been done before,” Jones remembers. “So we got one of those lasers up here [in Schenectady] and I figured out a way to join copper to aluminum, and that ended up being one of the first patents I got.”

Jones went on to develop laser beams powerful enough to cut steel, titanium, and nickel-based alloy, and was one of the first to find ways to use lasers for industrial materials processing, the basis for 3D printing, among other breakthroughs. His fiber-optic laser systems made lasers much more convenient for industrial applications.

His decades of innovative work with lasers were recognized in 2017 when he was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame, an institution that counts Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla, and the Wright brothers among its members. In 2020 he received the ICON award, presented by GE’s African American Forum, which acknowledges GE employees for their outstanding accomplishments in leadership and excellence in and outside the United States, for his work at GE and in the Black community. Jones was inducted into the National Academy of Engineering in 2001, and the following year he received the Coolidge Award, named after one of GE’s early research pioneers and directors, William Coolidge, and the highest individual honor a GE scientist and engineer can receive.

These days, Jones is still working with lasers, but with a focus on healthcare. He’s been collaborating with other researchers at Cambridge University in England on a way to repair a critical component of X-ray machines. “It might lead to driving down the cost of using an X-ray machine in medicine,” he says.

Passing the Torch

Since joining GE Research in 1974, Jones has been seriously tempted to leave only once — when he was offered leadership of the mechanical engineering department at his alma mater, University of Michigan.

“That was a tough call,” he says today. “But I’ve been able to do some things here that I probably wouldn’t have been able to do otherwise and work with amazing people.”

Jones has always been driven to devote time to working with children. He regularly speaks about his life and career at elementary, middle, and high schools, and he’s very involved with Camp Invention, a National Inventors Hall of Fame program that encourages young students to explore science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. And he’s still receiving fan mail thanking him for being an inspiration.

“I got a note just a couple of days ago from a man who is an engineer because of me,” Jones marvels. “I had no idea.”

That interest in paying it forward has brought him full circle. At one point, he returned to his elementary school at Aquebogue, to inspire students to try their hardest and urge them to never give up. Jones brought along a book Cheryl Weinstein had written about him, also called Never Give Up — which he has plans to update with a few more chapters. GE paid for enough books to be printed so that all the students could take home a copy. As he began to talk, the GE Research veteran spotted a familiar face in the audience: Mrs. DeFriest, retired and in her 80s, had come back to school to hear him. Afterward, Jones had a chance to talk with her.

“I mentioned what a big influence she had on me, so she knew, and she was very happy to see that her left-handed student had done all right,” Jones says.

Mrs. DeFriest’s former student intends to continue doing “all right” for as long as he can. At 82, he has no plans to retire.

“I love my work,” Jones says. “You don’t know what idea you might come up with that’s going to make a difference in people’s lives.”