Hire the Best People, Teach Them Through the Work: The Engineering Design Center in Warsaw Hits a 25-Year Milestone

April 03, 2025 | by Chris Norris

Situated on Warsaw’s historic Institute of Aviation campus, located right next to Fryderyk Chopin Airport, the GE Aerospace Engineering Design Center is what you’d expect in one of Europe’s biggest engineering hubs: 12 buildings, eight laboratories, and a bevy of test rooms, classrooms, and offices spread across roughly 33,000 square feet. Yet when Szymon Piwowarski first came to work here, in 2001, the center occupied less than a floor of a single building on a lonely stretch of Krakowska Avenue.

“Much of the campus looked sort of abandoned,” he recalls.

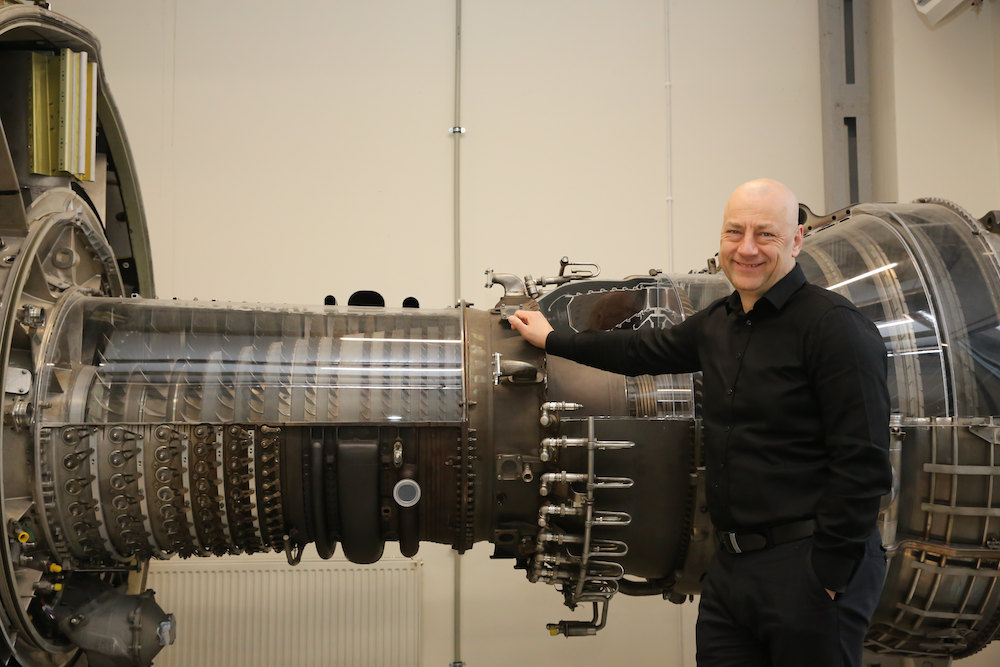

Twenty-five years later, Piwowarski is the executive engineering manager of the CF6 engine program, having followed a career trajectory that closely tracks the remarkable evolution of the center itself, which helped transform both Polish aviation and the professional lives of some of the nation’s most talented engineers.

Calling All Engineers!

At the turn of the millennium, Poland was recovering from half a century of Communist rule and the paralyzing recession of the 1990s. The post–Cold War military drawdown had dramatically reduced government support for aerospace, and there were few employment options for ambitious engineers in many fields. Back then “there were practically no companies offering global projects to engineers in Poland,” recalls Dorota Dorn-Okoń, the chief consulting engineer at the center.

Piwowarski’s parents and younger brother were urging him to follow them into the more reliable field of civil engineering. But he grew up obsessed with aviation and was determined to find work as a mechanical engineer, ideally in aerospace. After quitting his job as a teaching assistant at a technical university and moving to Warsaw, he saw a newspaper ad, applied for the job, and started work at GE Aerospace’s new center on April 1, 2001. Two weeks later, he was on a plane to the U.S. for 11 months of training at the company’s headquarters in Cincinnati — a steep introduction into the business that came with a few culture shocks.

For instance, that flight from Warsaw to Ohio was, believe it or not, Piwowarski’s first time on a jet plane. He and his colleagues were all in their mid-20s. “The majority were hired fresh out of university,” he says.

One day, on their free time, he and some Polish colleagues “met a group of other Poles in the [Cincinnati] area and were talking for a while before they asked us what we were doing there. They’d assumed we were working in construction, or at McDonald’s, or the amusement park,” he recalls. “When we told them we were engineers, they said, ‘No, you’re lying! There’s no Polish engineers working in the U.S.!’’’

Piwowarski periodically returned home during his nearly yearlong training period, where he focused on heat transfer technology in jet engines, including the GEnx. When he did, he noticed more fresh faces at the center in Warsaw — including, at one point, an entire university class of newly graduated engineers. Within a year, the center grew to 100 employees. Two years later, the head of GE Aviation at the time visited and was so impressed he called for the center to double its roster.

GE Aerospace’s Warsaw Campus Grows

When she was young, Dorn-Okoń would accompany her mother to her job at the government’s Institute of Aviation, where she operated some of the most advanced lab equipment in communist Poland. “At seven years old, I’d be sitting with her in front of this huge microscope,” recalls Dorn-Okoń, who went on to earn a material sciences degree and complete an internship at the institute.

Years later, in 2006, Dorn-Okoń received a call from one of the institute’s new tenants, GE Aerospace. “They said they had no one there who knew how to operate the microscope,” she recalls. After she joined the company, she found a very different energy from the place she’d known as a child. “At the institute, there had been a lot of distinguished professors, mostly academic,” Dorn-Okoń says. “The GE Aerospace campus was full of people who had just graduated, with maybe five experienced employees. We started off with a real start-up vibe.”

Initially, Dorn-Okoń led the materials team. As the Warsaw site came into its own, she took on managing larger and larger sections, gaining experience in different areas. (By 2014, the team in Warsaw had become significantly involved in design work and providing field support for the CF6 engine throughout its entire life cycle and had expanded to about 450 employees.) Like Piwowarski, she grew along with the center. They were no longer contractors for GE Aerospace but full-fledged employees working with some of the company’s global partners. “We had gone from backstage to the front stage,” says Piwowarski.

“We Own the Entire Life Cycle of the Engine”

Helping to oversee the longest-running jet engine program in commercial aviation history has its advantages. For example, the CF6, which started flying in 1971, still has 4,400 engines in operation. This is why Piwowarski considers it the ideal engine for training new engineers. “People do a tremendous amount of learning while they work on it,” he says. “You get the best people, teach them through the work, and after a few years watch them fly away” to work on different engine programs.

While the microscope her mother used now resides in a museum, Dorn-Okoń is also helping to lead its former home into the future. These days, she presides over a world-class laboratory that employs some 30 workers and uses three electron microscopes. In her role as chief consulting engineer, she advises fellow engineers with the top-tier designation “control title holder” (CTH). Twenty years ago, GE Aerospace’s Warsaw site had one senior engineer; today it has 115 CTHs.

“We have the capability to design engines, like in our Catalyst program,” Dorn-Okoń says, referring to the advanced turboprop engine that was recently certified by the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration. “We have people that work with customers, that design engines, that work with parts suppliers, that work with engine assembly, engine testing. We own the entire life cycle of the engine.”

As much of GE Aerospace’s engineering center has evolved, you can still see remnants of the past on the Institute of Aviation grounds, with aircraft from its proud 100-year history dotting a road running through the campus. Not so Warsaw itself, which has seen a remarkable transformation over the past two decades. During a recent 25th anniversary celebration, the GE Aerospace logo was projected onto one of Warsaw’s many skyscrapers, none of which existed in 2000, when both the center and the nation were still emerging from their post–Cold War history.

“Here, the Future of Flight team is working on engines that will fly in 10 or 20 years,” Dorn-Okoń says. “This team just keeps on growing.”