Extraordinary Together: GE Aerospace and Safran Aircraft Engines Celebrate 50th Anniversary of CFM International

September 23, 2024 | by Jay Stowe

Sometimes great minds really do think alike. When GE Aerospace and Safran Aircraft Engines signed the agreement in 1974 that created CFM International, a 50-50 joint venture between the two companies, they intended to rewrite the playbook for commercial aircraft engine manufacturing. Now, 50 years on, as CFM marks more than 1.3 billion engine flight hours across its CFM56 and CFM LEAP engine lines, the stats speak for themselves.

CFM56 engines power more than 14,650 commercial and military aircraft across more than 650 operators and are the industry leader in terms of reliability and durability. As the fleet reaches eight years in service, LEAP engines power more than 3,500 aircraft for nearly 160 operators and are rapidly maturing, with departure reliability rates comparable to those of the CFM56. All told, since the company was founded, more than 54,000 CFM engines have been ordered, and more than 42,500 delivered. And through the Revolutionary Innovation for Sustainable Engines (RISE) technology demonstration program, CFM aims to design a new powerplant that can reduce fuel consumption and carbon emissions by at least 20% compared with current commercial engines.

Which makes this the perfect time to take a look back at the important milestones that have helped CFM International get to where it is today: the most prolific jet propulsion company in aviation history.

Timeline of GE Aerospace and Safran Aircraft Engines’ Partnership

1970

The partnership between GE Aerospace and France’s government-owned Safran Aircraft Engines (then known as Snecma) is first broached in the cocktail lounge at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel in Boston in 1970. Over drinks, three French executives make an offer that the GE Aerospace execs can’t refuse: the idea to team up and build a new turbofan engine in the 20,000-pound thrust class to compete in the single-aisle commercial jet market. Ed Woll, former head of engineering at GE Aircraft Engines Business Group, attends the meeting with company president Gerhard Neumann and corporate counsel Jim Sacks. “You could have bowled us over with a feather,” Woll will later recall.

The offer does not come completely out of the blue. After launching the CF6-6 widebody engine program in 1967, GE Aerospace received its first customer orders to power the McDonnell Douglas DC-10 and, a year later, the new A300 passenger jet from Airbus. This is what initially led Safran Aircraft Engines and GE Aerospace to work together beginning in 1969: The two companies set up a revenue-sharing arrangement where Safran Aircraft Engines would produce engine parts for CF6-50-powered DC-10s and A300s sold in Europe.

1971

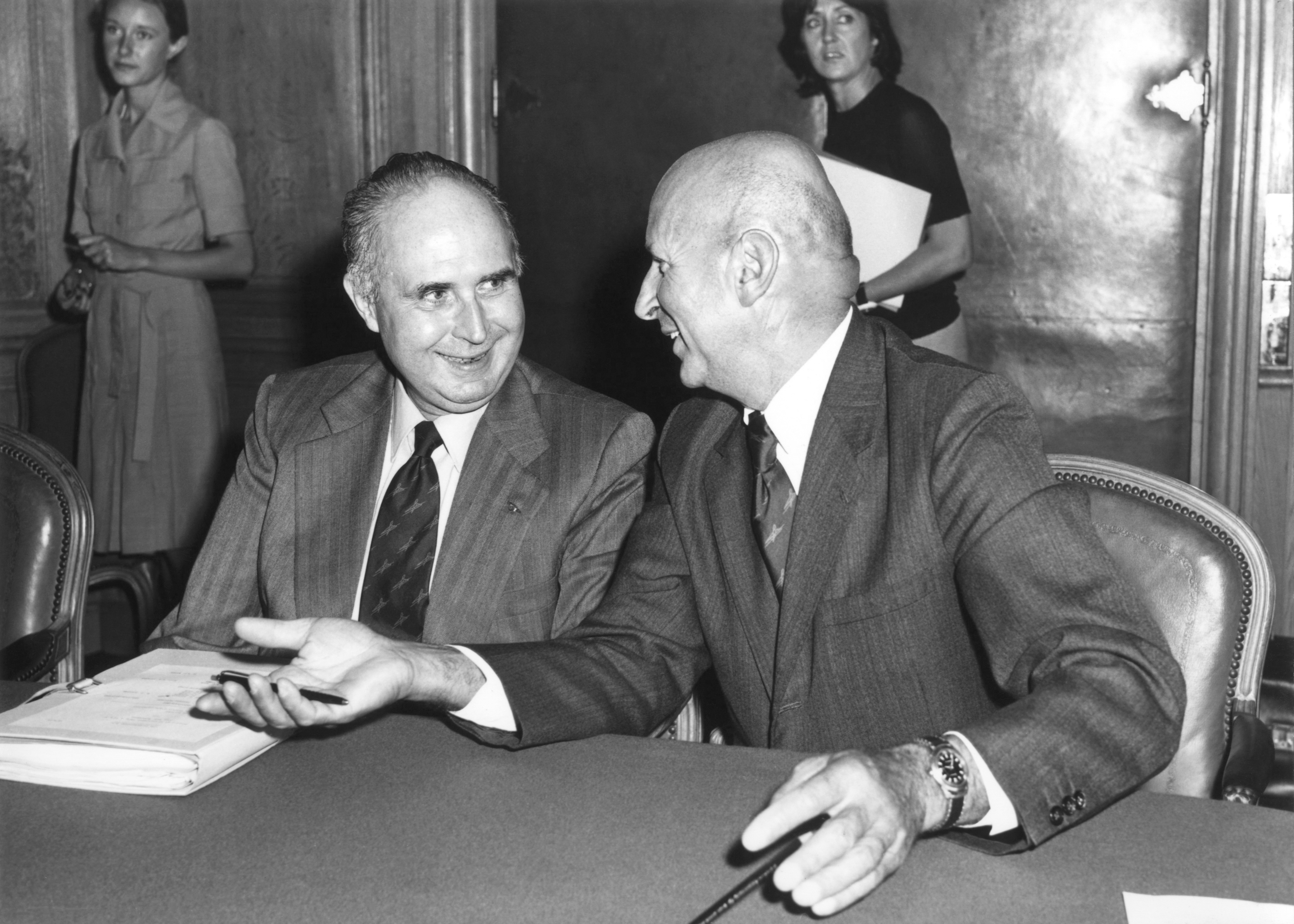

When Neumann and Safran Aircraft Engines’ new president, René Ravaud, eventually meet at the Paris Air Show in 1971, they quickly establish a strong bond. Neumann left Germany in the late 1930s and worked as an ace airplane mechanic with the American Volunteer Group (aka “Flying Tigers”) in China during World War II; Ravaud, an experienced aerospace engineer, was also a World War II hero who had lost his right arm during the Allied bombing of Brest Harbor in 1944. “He and I clicked from the very first moment we met,” Neumann will later write. It’s the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

1974

GE Aerospace and Safran Aircraft Engines have to overcome numerous hurdles before sealing the deal. The U.S. government initially rejects GE’s application to export its F101 engine core for joint commercial development with Safran Aircraft Engines, because the engine powers the U.S. Air Force B-1 bomber. Ultimately, with support from U.S. President Richard Nixon, the government relents, and in 1974 GE Aerospace and Safran Aircraft Engines sign the agreement that formally establishes CFM International as a joint 50-50 company charged with developing and selling the CFM56 engine family. The “CF” in CFM comes from GE Aerospace’s use of the letters to designate a “commercial turbofan.” The “M” is from M56, Safran Aircraft Engines’ original designation for the new engine.

1979

Safran Aircraft Engines is charged with designing and producing the front fan and low-pressure turbine (LPT) system; GE Aerospace oversees the engine core — comprising the high-pressure compressor (HPC), combustor, and high-pressure turbine (HPT). Despite successful ground and flight testing, the CFM56 engine goes for five years without a single application. Hope nearly runs out. However, just two weeks before the entire program is set to be suspended, in March 1979, United Airlines, Delta Air Lines, and Flying Tiger cargo line order the CFM56-2 to re-engine a total of 110 McDonnell Douglas DC-8 aircraft, dubbed the “DC-8 Super 70” series. It’s not the new airplane application the founders have hoped for, but it provides a critical lifeline.

1980

Close on the heels of the DC-8 re-engining program, the U.S. Air Force selects the CFM56-2 (designated the F108 for military purposes) to re-engine its huge fleet of four-engine KC-135 refueling tankers. In short order, the French Air Force commits to do the same with its KC-135 tankers. To this day, the USAF remains one of CFM’s biggest customers.

1981

Boeing chooses the CFM56-3 as the sole powerplant for its new 737-300, the first model in its “classic” series of single-aisle commercial jets, later to include the 737-400 and -500. Installation of the CFM56-3 on the 737-300 requires some creativity: The size of the front fan is reduced. More importantly, to meet the 737’s low wing ground clearance, the accessory gearbox — usually mounted on the bottom of the engine — is moved to the side, giving the CFM-powered 737 nacelle its iconic oval shape. By the time the last 737 “classic” is delivered in 2000, almost 4,000 CFM56-3 engines will have been produced.

1982–84

The CFM56-2 officially enters into service in April 1982 when a Delta Air Lines DC-8 Super 70 makes its first commercial flight from Atlanta to Savannah, Georgia. Two years later, Airbus launches its first single-aisle jet, the A320, with the CFM56-5A, the first CFM engine equipped with a full-authority digital electronic control system (FADEC).

1988–89

The CFM56-5A enters service on the A320 with Air France. A year later, Airbus launches the A321, a stretch version of the A320, powered by the CFM56-5B.

1993

The CFM56-7B is launched as the sole engine for Boeing’s “Next-Generation” 737 series, starting with Southwest Airlines. The CFM56-7B model, which enters service with Southwest in 1997, marks the fastest fleet ramp-up in commercial aviation history. It will hold that distinction until the introduction of the LEAP engine in 2016. In 1999, Boeing 737s powered by CFM56-7 engines become the first single-aisle commercial jets to be granted 180-minute Extended Twin-Engine Operations (ETOPS) approval, allowing airlines to offer longer flights and more flexible routes.

2008

At the Farnborough Airshow in July, CFM announces the launch of the CFM LEAP-X engine development program for potential new single-aisle commercial aircraft. At the same time, GE Aerospace and Safran Aircraft Engines agree — four years before the partnership agreement is set to expire — to extend the 50-50 joint company to 2040. The renewed agreement ensures that engines in the 18,000-to-50,000-pound thrust class will be developed by CFM, with GE continuing to supply the engine core (compressor, combustor, and HPT) and Safran Aircraft Engines the fan, booster, and LPT.

2016

After eight years of intensive technological development, an Airbus A320neo owned by Pegasus Airlines becomes the first LEAP-powered commercial flight to taxi down the runway and take off. Over the next eight years, CFM’s LEAP program will experience the fastest ramp-up in aviation history.

The key to the LEAP’s success is its stable, advanced design. Equipped with Safran Aircraft Engines’ resin transfer molding (RTM) carbon composite fan blades and fan case, and GE Aerospace’s ceramic matrix composite (CMC) components, along with fuel nozzles produced using additive manufacturing technology, LEAP engines promise to save 15% in fuel and carbon emissions versus CFM56 engines, with some customers reporting up to 20% improvement in their LEAP-powered aircraft, compared with their prior-generation aircraft. LEAP-powered aircraft also have a 99.95% departure reliability rate. Since entry into service, the LEAP engine family, which fits all variants of Airbus A320neo, Boeing 737 MAX, and COMAC C919 passenger jets, has logged more than 60 million flight hours on more than 3,500 aircraft flying with nearly 160 operators worldwide, and has helped CFM customers reduce CO2 emissions (compared with the CFM56) by more than 35 million tons.

2019

With 37 years in service spread across six different models, the CFM56 engine family logs its billionth flight hour, a feat never before accomplished in aviation history. In addition, the CFM56 engine boasts a 99.98% departure reliability rate, a firm reputation for increased time on wing, and the record for the best-selling commercial engine ever.

2021

GE Aerospace and Safran Aircraft Engines unveil the CFM Revolutionary Innovation for Sustainable Engines (RISE) program. The aim is to develop disruptive technologies — including Open Fan engine architecture, a compact engine core, hybrid electric systems, and more advanced materials — to help the aviation industry achieve the goal of net zero carbon emissions by 2050. Currently, the RISE program is advancing technologies to support flight that is at least 20% more fuel-efficient, resulting in 20% lower carbon emissions than current commercial engines. To date, more than 250 tests have been completed on the RISE program technologies.

“The work happening today on test rigs and with research partners around the world represents an unprecedented level of new technology development in CFM’s history,” says Gaël Méheust, president and CEO of CFM International. “As CFM celebrates its 50th anniversary, we are acting on our clear ambition to make air transport more sustainable. With the RISE program, CFM will once again change the way that people fly.”