Cold War Child: How the GE J47 Became the World’s Most Produced Jet Engine

July 1, 2019 | by Rick Kennedy

The end of World War II in 1945 led to a predictable drawdown of military mass production and deliveries across America but the war had introduced the brave new world of jet power, with several countries on both sides of the bloody conflict introducing fighter jets into combat. There was no turning back: The race was on.

As the war ended, the U.S. government began aggressively funding development contracts for an array of jet-powered fighter and bomber concepts. GE Aviation’s Lynn, Massachusetts, operation seized the day. Having introduced America’s first jet engine in 1942, GE Lynn’s early turbojets included the axial-flow J35 turbojet, which became America’s most popular military jet engine immediately after the war. In 1946, the team at Lynn took the bold step of proposing to the government a new axial-flow turbojet successor, called the J47, even before a specific aircraft was defined. Times being what they were, it didn’t take long for GE to sell the engine development concept to the military.

With legendary GE engineer Neil Burgess leading the project, the Lynn engineers quickly designed a J35-sized, axial-flow J47 that incorporated compressor and turbine sections for higher-pressure ratios, as well as lightweight components needed to produce 5,000 pounds of thrust.

The J47 was a bold step forward. Touted as “the all-weather engine,” the J47 was the first turbojet with an anti-icing system in which hollow frame struts allowed passage of heated air from the compressor. Developed largely by Burgess and Joe Buechel, the anti-icing system was key to meeting demanding missions of fighter jets at high altitude. GE validated the system in a test cell for several months atop Mount Washington in New Hampshire’s White Mountains, where winds can gust to 140 miles an hour in the bitter cold. To boost aircraft power at takeoff and for fast acceleration at altitude, the J47 incorporated the first electronically controlled afterburner—using vacuum tubes—a design spearheaded by Ed Woll, a young Lynn engineer who would continue to play a central role in the company’s growing jet engine enterprise.

However, with the U.S. economy in post-war flux, a few corporate leaders with GE began to question the long-term business potential for the new jet propulsion industry. The Lynn team wouldn’t hear it.

As J47 production got underway in Lynn in 1948, general manager Harold Kelsey pursued a second assembly line to create more in-house production capacity for the company’s new mainstay turbojet. Encouraged by the U.S. Air Force, GE selected the former Wright Aeronautical plant in Lockland, Ohio, which had been mothballed after World War II. That same year, J47 engines were installed in a North American F-86 Sabre, which set a world speed record of 670.9 miles per hour.

Despite this technical success, a huge challenge loomed. With defense cutbacks growing more severe by 1949 under President Harry S. Truman, GE considered closing the new Lockland operation as prospects for the J47 to become a large production program dimmed. Then, seemingly overnight, the Korean War broke out in June 1950 and demand for the J47 surged.

The F-86 Sabre became the key American fighter jet in the Korean War. The first swept-wing fighter in the USAF arsenal, the F-86 was fast and maneuverable, bolstered by the J47 afterburner. The F-86 established air superiority in Korea with an estimated 14-to-1 kill ratio in combat with MiG-15 fighters. The USAF’s other prominent J47-powered jet in Korea was the high-speed, intimidating Boeing B-47 Stratojet.

The Korean War represented the first time there was true air-to-air combat between jet-powered fighters, and all the world was watching. Not even the greatest GE optimists could have imagined how omnipresent the J47 turbojet would become in U.S. military aviation over the next 10 years as the Cold War standoff with the Soviet Union grew. By the mid-1950s, having proven itself in the skies over Korea, the J47 powered most front-line U.S. military jets—13 applications in all, including the F-86, the B-47, the Convair B-36 Bomber, the North American B-45 Tornado, the Martin B-51 Bomber, and the Northrop YB-49 Flying Wing.

During that period, Lockland plant employment swelled from 1,200 employees in 1949 to 8,000 employees by 1954 behind an aggressive recruitment program throughout the region. The J47 engineering headquarters moved to Lockland—soon to be renamed the Evendale facility—as it became America’s most-produced jet engine. For the production ramp, several manufacturing innovations were introduced, including vertical engine assembly to maintain compressor rotor balance and stability.

The J47 became GE Aviation’s financial bread-and-butter. By 1953-1954, production reached an astounding 975 engines per month. In addition to the Lockland and Lynn plants, the engine was produced under license by U.S. automotive companies Studebaker and Packard auto factories. The unprecedented 10-year production ended in 1956. By then, FIAT in Italy and Ishikawajima-Harima in Japan had joined GE and the two auto companies in producing the engine.

In total, more than 35,000 J47s were built, making it the most produced jet engine in aviation history. The program firmly established GE Aviation as a world leader in jet propulsion, a position the company would continue to enhance over the next six decades.

As the war ended, the U.S. government began aggressively funding development contracts for an array of jet-powered fighter and bomber concepts. GE Aviation’s Lynn, Massachusetts, operation seized the day. Having introduced America’s first jet engine in 1942, GE Lynn’s early turbojets included the axial-flow J35 turbojet, which became America’s most popular military jet engine immediately after the war. In 1946, the team at Lynn took the bold step of proposing to the government a new axial-flow turbojet successor, called the J47, even before a specific aircraft was defined. Times being what they were, it didn’t take long for GE to sell the engine development concept to the military.

With legendary GE engineer Neil Burgess leading the project, the Lynn engineers quickly designed a J35-sized, axial-flow J47 that incorporated compressor and turbine sections for higher-pressure ratios, as well as lightweight components needed to produce 5,000 pounds of thrust.

The J47 was a bold step forward. Touted as “the all-weather engine,” the J47 was the first turbojet with an anti-icing system in which hollow frame struts allowed passage of heated air from the compressor. Developed largely by Burgess and Joe Buechel, the anti-icing system was key to meeting demanding missions of fighter jets at high altitude. GE validated the system in a test cell for several months atop Mount Washington in New Hampshire’s White Mountains, where winds can gust to 140 miles an hour in the bitter cold. To boost aircraft power at takeoff and for fast acceleration at altitude, the J47 incorporated the first electronically controlled afterburner—using vacuum tubes—a design spearheaded by Ed Woll, a young Lynn engineer who would continue to play a central role in the company’s growing jet engine enterprise.

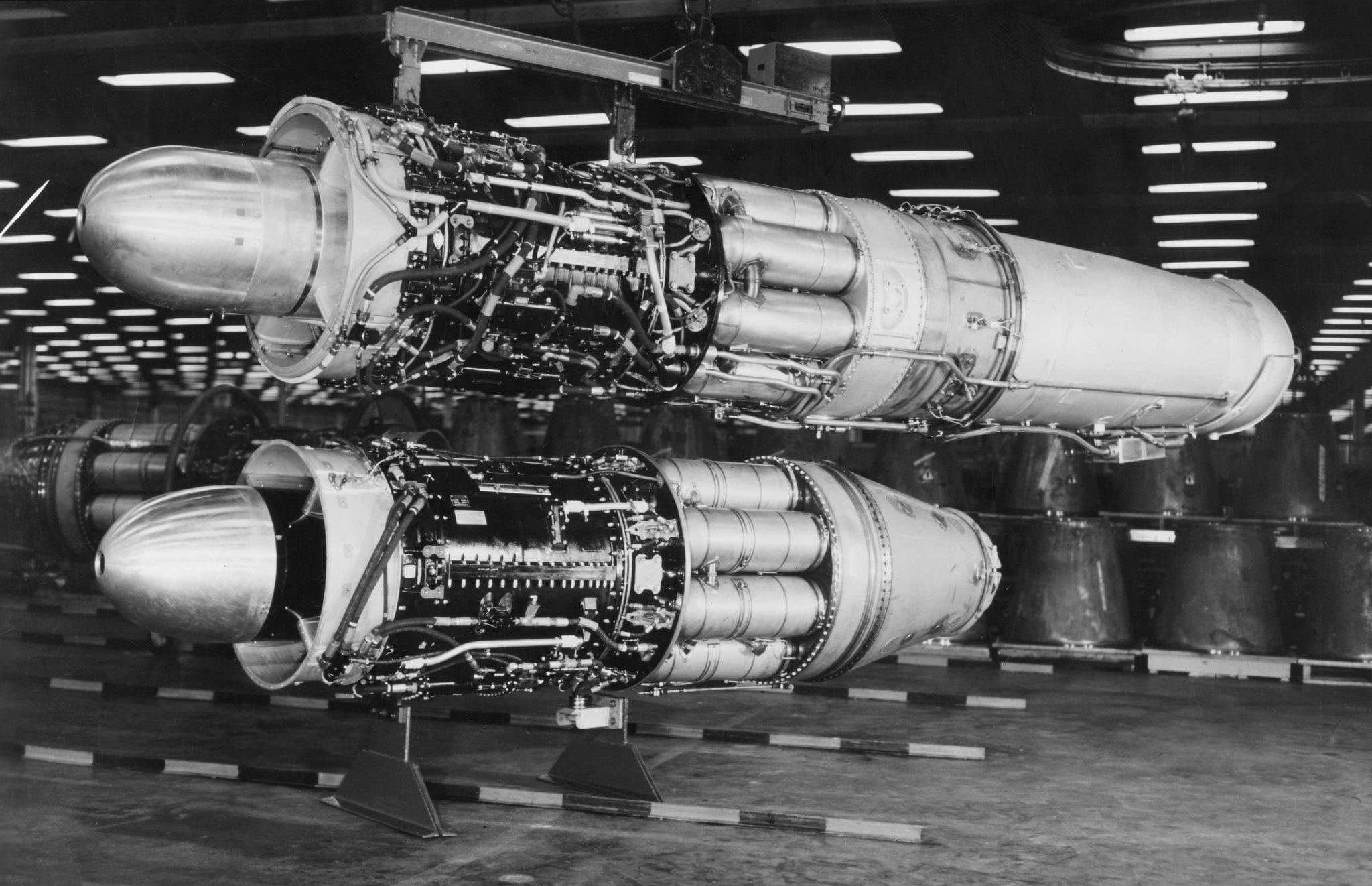

Above: J47s rolling off the line in 1948 at the Evendale plant. Top: An F-86 Sabre.

Above: J47s rolling off the line in 1948 at the Evendale plant. Top: An F-86 Sabre.

However, with the U.S. economy in post-war flux, a few corporate leaders with GE began to question the long-term business potential for the new jet propulsion industry. The Lynn team wouldn’t hear it.

As J47 production got underway in Lynn in 1948, general manager Harold Kelsey pursued a second assembly line to create more in-house production capacity for the company’s new mainstay turbojet. Encouraged by the U.S. Air Force, GE selected the former Wright Aeronautical plant in Lockland, Ohio, which had been mothballed after World War II. That same year, J47 engines were installed in a North American F-86 Sabre, which set a world speed record of 670.9 miles per hour.

Despite this technical success, a huge challenge loomed. With defense cutbacks growing more severe by 1949 under President Harry S. Truman, GE considered closing the new Lockland operation as prospects for the J47 to become a large production program dimmed. Then, seemingly overnight, the Korean War broke out in June 1950 and demand for the J47 surged.

The F-86 Sabre became the key American fighter jet in the Korean War. The first swept-wing fighter in the USAF arsenal, the F-86 was fast and maneuverable, bolstered by the J47 afterburner. The F-86 established air superiority in Korea with an estimated 14-to-1 kill ratio in combat with MiG-15 fighters. The USAF’s other prominent J47-powered jet in Korea was the high-speed, intimidating Boeing B-47 Stratojet.

The Korean War represented the first time there was true air-to-air combat between jet-powered fighters, and all the world was watching. Not even the greatest GE optimists could have imagined how omnipresent the J47 turbojet would become in U.S. military aviation over the next 10 years as the Cold War standoff with the Soviet Union grew. By the mid-1950s, having proven itself in the skies over Korea, the J47 powered most front-line U.S. military jets—13 applications in all, including the F-86, the B-47, the Convair B-36 Bomber, the North American B-45 Tornado, the Martin B-51 Bomber, and the Northrop YB-49 Flying Wing.

Touted as “the all-weather engine,” the J47 was the first turbojet with an anti-icing system in which hollow frame struts allowed passage of heated air from the compressor.

Touted as “the all-weather engine,” the J47 was the first turbojet with an anti-icing system in which hollow frame struts allowed passage of heated air from the compressor.

During that period, Lockland plant employment swelled from 1,200 employees in 1949 to 8,000 employees by 1954 behind an aggressive recruitment program throughout the region. The J47 engineering headquarters moved to Lockland—soon to be renamed the Evendale facility—as it became America’s most-produced jet engine. For the production ramp, several manufacturing innovations were introduced, including vertical engine assembly to maintain compressor rotor balance and stability.

The J47 became GE Aviation’s financial bread-and-butter. By 1953-1954, production reached an astounding 975 engines per month. In addition to the Lockland and Lynn plants, the engine was produced under license by U.S. automotive companies Studebaker and Packard auto factories. The unprecedented 10-year production ended in 1956. By then, FIAT in Italy and Ishikawajima-Harima in Japan had joined GE and the two auto companies in producing the engine.

In total, more than 35,000 J47s were built, making it the most produced jet engine in aviation history. The program firmly established GE Aviation as a world leader in jet propulsion, a position the company would continue to enhance over the next six decades.

A 1948 GE ad touting the record-breaking abilities of the J47, which were installed in a North American F-86 Sabre, setting a world speed record of 670.9 miles per hour.

A 1948 GE ad touting the record-breaking abilities of the J47, which were installed in a North American F-86 Sabre, setting a world speed record of 670.9 miles per hour.