No engine in jet propulsion is quite like GE’s tiny J85 turbojet. Originally designed in 1954, the J85 is expected to power U.S. military aircraft until at least 2040.

That’s not a typo: GE had delivered more than 12,000 J85 engines and its commercial engine variants by the end of its production run in 1988. Yet the U.S. Air Force and NASA expect to keep J85-powered T-38 trainer jets in operational service until 2040 and beyond. That means the J85 will be in operational service for 85 years!

GE Aviation continues to steadily produce supplies for the J85. In May, the company was awarded a $394 million contract from the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) to provide J85 engine supplies for the United States Air Force and Navy.

“We’re very excited about supporting the U.S. Air Force and Navy with a reliable engine that has been flown by generations of pilots, proudly built by generations of GE employees,” said Al DiLibero, GE Aviation’s vice president and general manager of medium combat & trainer engines.

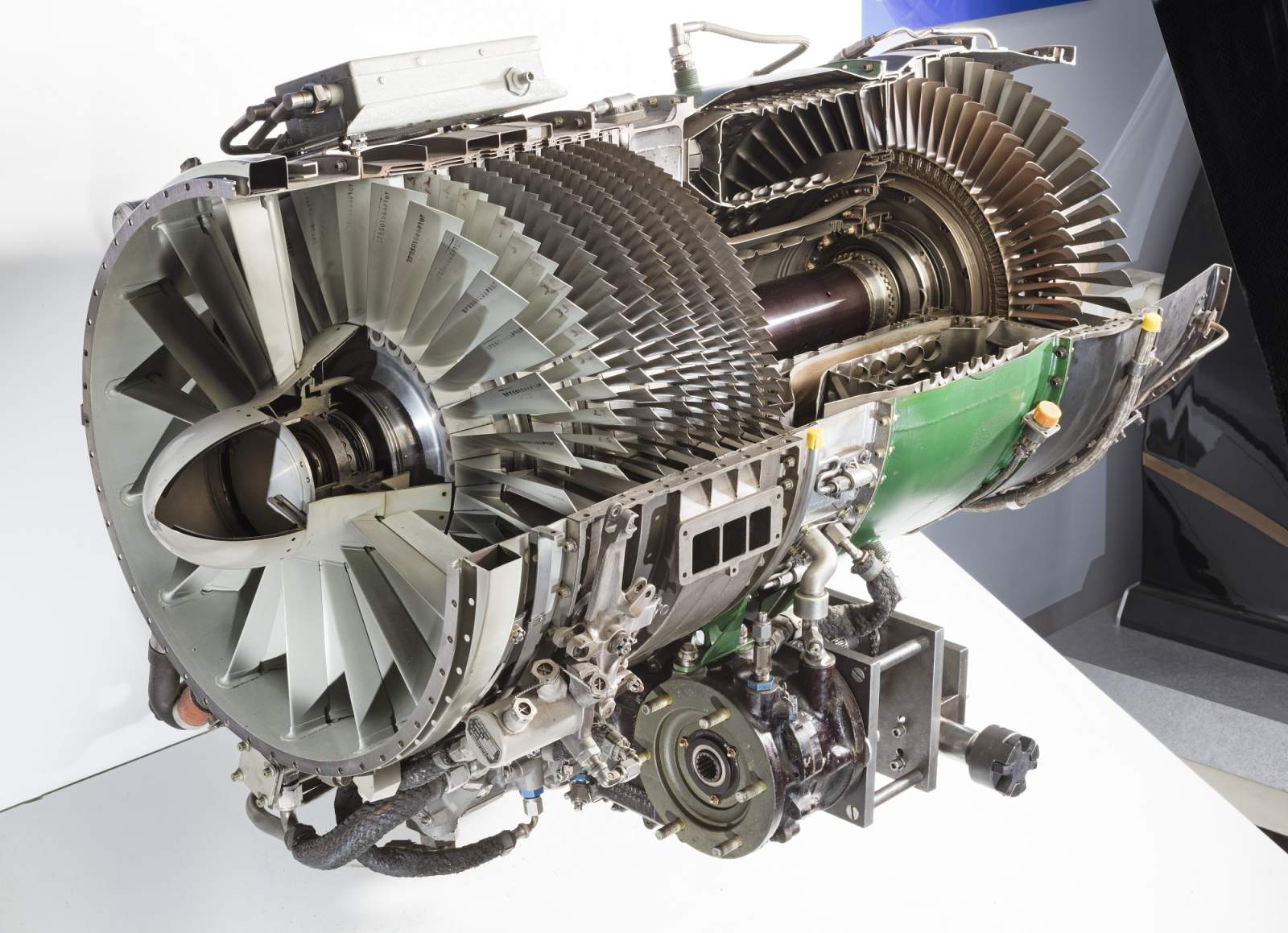

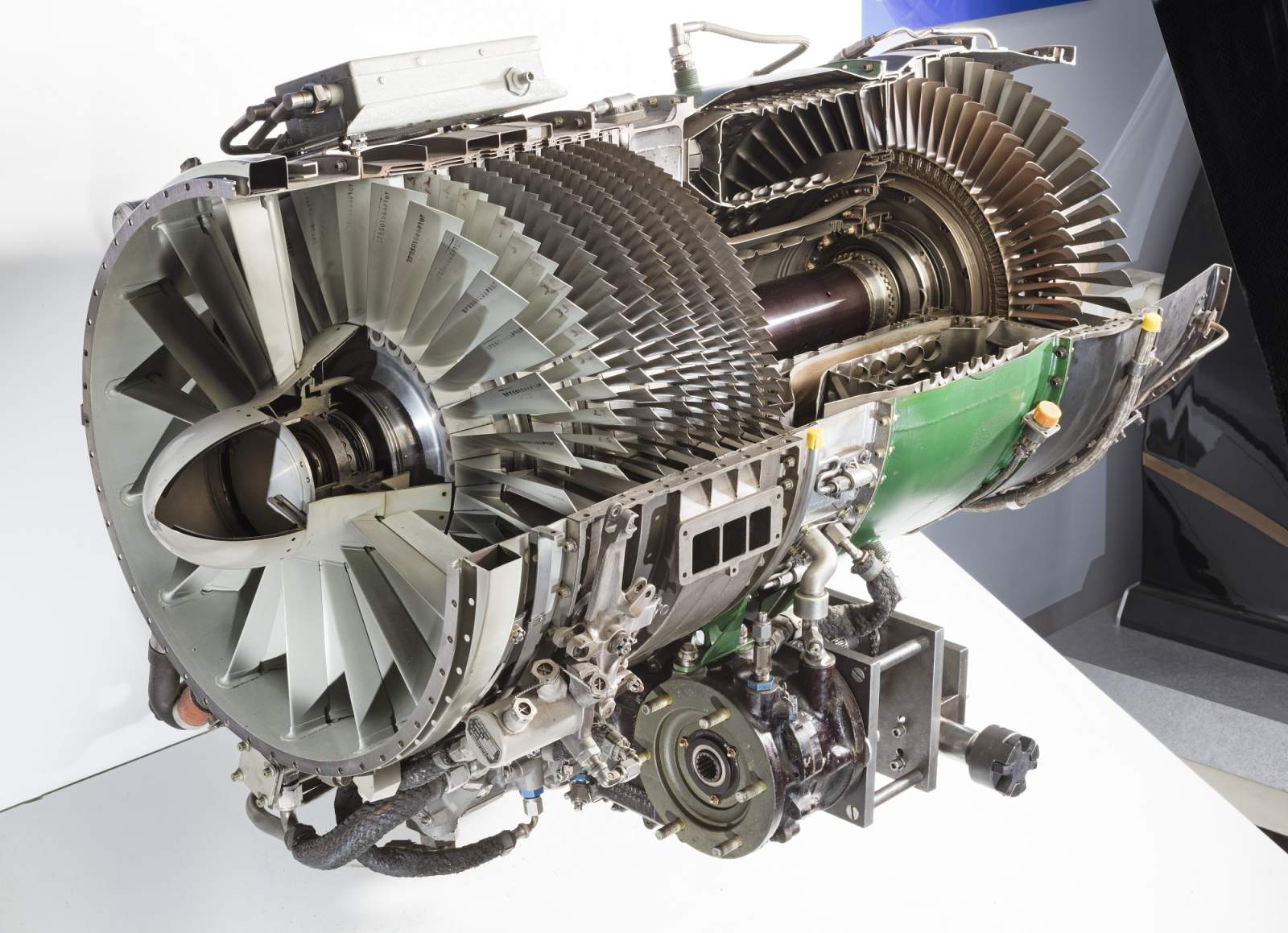

Not bad for a jet engine that’s all of 18 inches wide and 45 inches long. For many years, the J85 had the highest thrust-to-weight ratio (8:1) of any jet engine in aviation. Let’s just call it “The Little Tough Guy.”

The Little Tough Guy’s story begins in the early 1950s when Jack Parker and Ed Woll, leaders of GE Aviation’s operation in Lynn, Massachusetts, believed that a small turbojet in the 2,500-pound thrust class could secure several military aircraft applications over time.

They were right. However, after proposing a small turbojet engine to the USAF in 1954, the first application was not what they expected. The USAF financed J85 development for the GAM-72 Green Quail missile decoy installed in the Boeing B-52 bomber. The strategy was to release the air-launched missile decoy just before the B-52 entered enemy airspace to confuse the defense radar network in differentiating between the larger bomber and the small missile decoy. The J85-powered missile decoy was revealed to the public in late 1958 after several successful launches.

Following the success of the GAM-72, the Parker-led team in Lynn chased aircraft applications for the efficient J85 engine, which was tested in 1957 with an afterburner for supersonic flight. Northrop selected the J85 for both of its “sister supersonic military jets” under development: the twin-engine N-156F Freedom Fighter, later designated the F-5, and the USAF’s twin-engine T-38 Talon, the first supersonic military trainer.

With an 8-to-1 thrust-to-weight ratio—the highest of any jet engine in production at the time—Northrop publicly hailed the J85 for making both aircraft possible. The engine was designed to produce 2,950 pounds of non-afterburning thrust. For the Northrop jets, however, The Little Tough Guy became the first small turbojet to operate with an afterburner, which made the engine capable of producing up to 5,000 pounds of thrust.

Designed as a low-cost alternative for America’s partner nations in the Cold War, the F-5 was initially self-funded by Northrop. The aircraft was lighter and smaller than U.S. fighter jets, designed for short-range missions at high-speeds, and capable of rapid climb rates. In February 1959, the U.S. government provided $7 million to Northrop for the F-5, marking the first time the U.S. financially supported the development of a supersonic military jet designated specifically for its allies.

In 1959, the T-38 was flight-tested at Edwards Air Force, California, allowing instructors to teach pilots the fundamentals of supersonic flying, including takeoff and landing, special nighttime missions, and aerobatics. That July, the F-5 began its flight tests. It would soon become wildly successful around the world.

Building upon the high-volume of the popular T-38 and F-5, the Lynn team pursued a J85 commercial variant for a new generation of business jets. The CJ610, a non-afterburning turbojet, was a J85-derived companion to the 4,000-pound thrust CF700, which had an aft-mounted fan like the larger CJ805-23 turbofan for the Convair 900.

In 1963, Bill Lear captured the public’s imagination by launching the “Model 23,” a small executive airplane powered by the CJ610 turbojet. Among the first luxury aircraft to be mass-produced and targeted for business executives, the Lear Jet symbolized American “jetsetter” affluence and swashbuckling innovation. Promoted in marketing literature as the “500-mile an hour executive jet,” it could carry seven passengers and 300 pounds of luggage, and it set numerous speed records for business jets. In 1966, a weary Bill Lear and his crew ended a three day, 23,286-mile journey, the first officially-sanctioned, round-the-world flight for a business jet.

The CJ610’s turbofan sister, the CF700, was also launched on the Dassault Falcon 20, the European luxury business jet, in 1963. A year later, the CF700 became the first turbofan to power business jets. As it turns out, GE’s Little Tough Guy powered most of the era’s business jets.

By the end of its production run in 1988, the J85 had been redesigned and enhanced four times, and the small F-5 fighter jet had become the standard air defense aircraft for more than 25 nations. In 2001, the USAF awarded a $601 million contract for hardware kits to upgrade 1,202 J85 engines powering the ageless T-38 Talon trainer. The upgrade kit, including a redesigned compressor rotor and stator assembly, an improved HPT, and new afterburner liner, was intended to extend the J85 service life well into the 21st century. And that’s exactly what it did.

In 2018, the USAF announced the selection of a new trainer aircraft from Boeing and Saab called the T-7A Red Hawk, powered by GE’s venerable F404 engine. That does not, however, mean the end of the line for the J85. First deliveries of the T-7A Red Hawk are expected in 2025 with USAF squadrons fully outfitted with the aircraft in the 2035 timeframe. Meanwhile, NASA and other operators are expected to operate J85-powered T-38s beyond that.

So, The Little Tough Guy will be around for a long time.

That’s not a typo: GE had delivered more than 12,000 J85 engines and its commercial engine variants by the end of its production run in 1988. Yet the U.S. Air Force and NASA expect to keep J85-powered T-38 trainer jets in operational service until 2040 and beyond. That means the J85 will be in operational service for 85 years!

GE Aviation continues to steadily produce supplies for the J85. In May, the company was awarded a $394 million contract from the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) to provide J85 engine supplies for the United States Air Force and Navy.

“We’re very excited about supporting the U.S. Air Force and Navy with a reliable engine that has been flown by generations of pilots, proudly built by generations of GE employees,” said Al DiLibero, GE Aviation’s vice president and general manager of medium combat & trainer engines.

Not bad for a jet engine that’s all of 18 inches wide and 45 inches long. For many years, the J85 had the highest thrust-to-weight ratio (8:1) of any jet engine in aviation. Let’s just call it “The Little Tough Guy.”

The Little Tough Guy’s story begins in the early 1950s when Jack Parker and Ed Woll, leaders of GE Aviation’s operation in Lynn, Massachusetts, believed that a small turbojet in the 2,500-pound thrust class could secure several military aircraft applications over time.

They were right. However, after proposing a small turbojet engine to the USAF in 1954, the first application was not what they expected. The USAF financed J85 development for the GAM-72 Green Quail missile decoy installed in the Boeing B-52 bomber. The strategy was to release the air-launched missile decoy just before the B-52 entered enemy airspace to confuse the defense radar network in differentiating between the larger bomber and the small missile decoy. The J85-powered missile decoy was revealed to the public in late 1958 after several successful launches.

Following the success of the GAM-72, the Parker-led team in Lynn chased aircraft applications for the efficient J85 engine, which was tested in 1957 with an afterburner for supersonic flight. Northrop selected the J85 for both of its “sister supersonic military jets” under development: the twin-engine N-156F Freedom Fighter, later designated the F-5, and the USAF’s twin-engine T-38 Talon, the first supersonic military trainer.

With an 8-to-1 thrust-to-weight ratio—the highest of any jet engine in production at the time—Northrop publicly hailed the J85 for making both aircraft possible. The engine was designed to produce 2,950 pounds of non-afterburning thrust. For the Northrop jets, however, The Little Tough Guy became the first small turbojet to operate with an afterburner, which made the engine capable of producing up to 5,000 pounds of thrust.

Designed as a low-cost alternative for America’s partner nations in the Cold War, the F-5 was initially self-funded by Northrop. The aircraft was lighter and smaller than U.S. fighter jets, designed for short-range missions at high-speeds, and capable of rapid climb rates. In February 1959, the U.S. government provided $7 million to Northrop for the F-5, marking the first time the U.S. financially supported the development of a supersonic military jet designated specifically for its allies.

In 1959, the T-38 was flight-tested at Edwards Air Force, California, allowing instructors to teach pilots the fundamentals of supersonic flying, including takeoff and landing, special nighttime missions, and aerobatics. That July, the F-5 began its flight tests. It would soon become wildly successful around the world.

Building upon the high-volume of the popular T-38 and F-5, the Lynn team pursued a J85 commercial variant for a new generation of business jets. The CJ610, a non-afterburning turbojet, was a J85-derived companion to the 4,000-pound thrust CF700, which had an aft-mounted fan like the larger CJ805-23 turbofan for the Convair 900.

In 1963, Bill Lear captured the public’s imagination by launching the “Model 23,” a small executive airplane powered by the CJ610 turbojet. Among the first luxury aircraft to be mass-produced and targeted for business executives, the Lear Jet symbolized American “jetsetter” affluence and swashbuckling innovation. Promoted in marketing literature as the “500-mile an hour executive jet,” it could carry seven passengers and 300 pounds of luggage, and it set numerous speed records for business jets. In 1966, a weary Bill Lear and his crew ended a three day, 23,286-mile journey, the first officially-sanctioned, round-the-world flight for a business jet.

The CJ610’s turbofan sister, the CF700, was also launched on the Dassault Falcon 20, the European luxury business jet, in 1963. A year later, the CF700 became the first turbofan to power business jets. As it turns out, GE’s Little Tough Guy powered most of the era’s business jets.

By the end of its production run in 1988, the J85 had been redesigned and enhanced four times, and the small F-5 fighter jet had become the standard air defense aircraft for more than 25 nations. In 2001, the USAF awarded a $601 million contract for hardware kits to upgrade 1,202 J85 engines powering the ageless T-38 Talon trainer. The upgrade kit, including a redesigned compressor rotor and stator assembly, an improved HPT, and new afterburner liner, was intended to extend the J85 service life well into the 21st century. And that’s exactly what it did.

In 2018, the USAF announced the selection of a new trainer aircraft from Boeing and Saab called the T-7A Red Hawk, powered by GE’s venerable F404 engine. That does not, however, mean the end of the line for the J85. First deliveries of the T-7A Red Hawk are expected in 2025 with USAF squadrons fully outfitted with the aircraft in the 2035 timeframe. Meanwhile, NASA and other operators are expected to operate J85-powered T-38s beyond that.

So, The Little Tough Guy will be around for a long time.